|

|

|

|

The

views expressed

on this page are soley those of the author and do not

necessarily

represent the views of County News Online

|

|

Heritage Foundation

Improving the

Quantity and Quality of America’s Volunteerism

Brian Fikkert

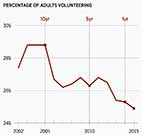

Volunteerism dropped in 2015, continuing a decade-long trend in which

the percentage of adults who volunteer has declined by a total of 3.9

percentage points. Regrettably, these recent declines are part of a

century-long decrease in rates of volunteerism in America,[1] a trend

rooted in fundamental issues that hinder not only the quantity, but

also the quality of our volunteerism.

One of the most important of these issues is widespread materialism:

the belief that happiness comes from acquiring more possessions.

Although the seeds of materialism have been present since America’s

inception, a combination of philosophical, economic, and social forces

in the past century has resulted in a culture that is increasingly

focused on material progress as the source of happiness.[2]

Materialism is necessarily self-centered, while volunteerism is

others-centered. Hence, it is not surprising that researchers are

finding materialistic people to be less likely to volunteer — a fact

that explains at least some of the decline in the quantity of

volunteerism in America.[3] But materialism also affects the quality of

our volunteerism. For example, consider volunteerism targeted at

alleviating poverty.

Because Americans tend to think of poverty in material terms, our

approaches to helping the poor often tend toward merely providing them

with material resources: dispensing food, ladling soup, and giving out

clothing. In times of crisis, such handouts are the appropriate

response, but when low-income individuals or communities are in a

chronic state of poverty, this approach amounts to treating symptoms

rather than addressing the underlying causes of their condition. There

are deeper forces at work that must be addressed.

If we listen carefully to the poor, we can hear them longing for more

than just greater consumption, for they commonly express feelings of

shame, inferiority, social isolation, and powerlessness. These problems

involve far more than a lack of material things, and simply handing out

more material resources cannot solve them.

While human beings are partly material — we have bodies and real

physical needs — both the wisdom of the ages and scientific evidence

teach us that human beings are hardwired for relationships: with God,

self, others, and the environment.[4] More often than not, it is the

brokenness in these foundational relationships that leads to material

poverty, but these relationships cannot be repaired by handouts of

material resources alone.[5] In fact, handouts can make these

relationships worse.

How Can a Material Approach to Poverty Do Harm?

Simply providing handouts of material resources to poor people can

exacerbate their feelings of shame and inferiority and undermine the

development of their own skills and resources. As a result, handouts

can render poor people even more powerless than they were before they

received the “help.”

Short-term trips to low-income communities abroad often provide prime

examples of this dynamic. Volunteers rush in to build houses and dig

wells — things that the community could do on its own — thereby

undermining local initiative, ownership, and stewardship. Similarly,

such trips often dispense clothing and shoes, which can undermine local

businesses and create dependence on the outsiders.[6]

Do More, But Do It Differently

Evidence and experience show that we need to use more relational

approaches, walking alongside poor people instead of treating them as

objects of our assistance.[7] This engages poor people as full

participants in the process, building on their assets and abilities in

order to restore their dignity and capacity. The goal in such an

approach is not simply to increase the material condition of poor

people, but also to help them experience greater flourishing in their

relationships with God, self, others, and the environment.

One example is the Circles of Support model.[8] In this approach, the

poor person chooses and leads a team of “allies” who surround the

person with encouragement, community, accountability, and various forms

of assistance. In addition, the allies provide access to crucial social

and professional networks and can even provide advocacy when systemic

injustice is an issue.

One key to more and better volunteerism is the rejection of materialism

in favor of a relational understanding of human nature. As we make this

shift, we open up possibilities for greater human flourishing both for

the helpers and for those who are being helped.

|

|

|

|