An Indiana school wants middle schoolers to start considering career choices now, but is the timing right?

From The Hechinger Report

by Liz Willen

January 23, 2022

INDIANAPOLIS — Before the pandemic, 14-year-old Kynadi Chandler, as is typical of middle schoolers, had career goals that were all over the place. She thought she might want to become a journalist. Or a nurse. She was also interested in studying culinary arts.

Last year’s isolating lockdown gave the eighth grader a more specific goal: She wants to become a psychologist or therapist of some kind. “I want people to know it’s okay to ask for help,’’ K.C., as she is known, told me. “I was struggling a bunch at home, and not being around other people let me realize what they are also going through. It made me want to help others.”

K.C. recalled the uncertainty, loneliness and chaos of coronavirus upheaval as she discussed potential career interests with school counselors and classmates at Northview Middle School on a rainy December morning. Many watched their parents get ill, lose jobs or try to work from home. When the kids returned to Northview in-person this fall, several expressed feeling angry and stressed. In a schoolwide poll, others said they had no trusted grown-up to speak with, and no idea what they wanted to do after high school.

Clearly, the pandemic is changing the outlook of kids K.C.’s age. “It really impacted how they view school and careers,’’ said Northview principal Steven Pelych, who analyzed the results. “Some students are a little bit lost about what their future holds.”

The virus is still surging in this racially diverse district of about 11,000 students in northern Indianapolis. But exploratory chats about future career interests with students here are part of a curriculum that begins with discussing things like self-confidence with counselors. Educators here and elsewhere in the country say it’s not too soon to prompt students to think far ahead, an idea backed by recent research. They also believe imagining the future might help students cope better with the present.

“We made a conscious decision to make the sixth-grade experience one where we expose children to everything,” said Rick Doss, the district’s director of secondary education. “Our objective and goal is really to make students and parents aware of all the options.”

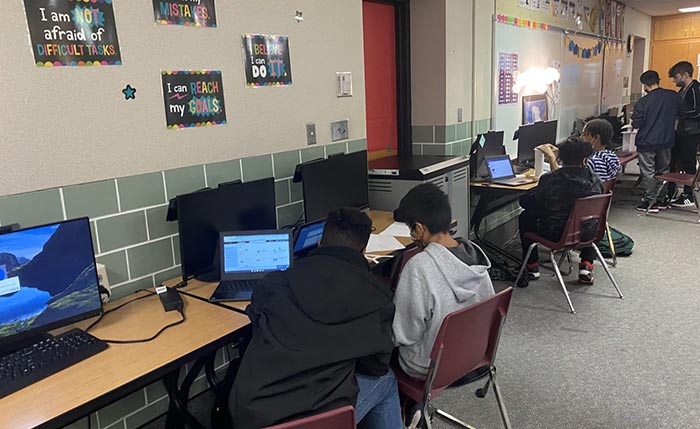

On the day I visited Northview, K.C. and her classmates were scrolling through Naviance for Middle Schools, a tool for assessing strengths and interests. Sixth graders can also take an elective version of AVID (Advancement Via Individual Determination), a nonprofit college and career readiness program. In seventh grade, they explore topics like personality type and career fit. In their final middle school year, eight graders attend a two-day career expo on the state’s fairgrounds, which was offered virtually last year.

Getting a jump start on career thinking in middle school, when academic performance often drops, is part of a growing trend. Recent research identifies these awkward years as a key time for setting future goals. Individual states and nonprofits are stepping-up their programs. In Indiana, even more help will be on the way once a pilot program, Indiana Career Explorer, a free online career and planning tool, ramps up in more middle schools.

The efforts come at a time at a time when fewer Indiana students are going to college, part of a national trend. A recent report found Indiana’s rates at their lowest in recent history. Just 59 percent of students here enroll after high school, a drop from a rate of 61 percent in 2018. College-going rates were even lower among Black, Hispanic and Latino, and low-income students. The majority of rural counties lost population over the last 10 years in this Rust Belt state and too many jobs are unfilled, prompting an array of new partnerships aimed at connecting employers to talent.

These are all good reasons to get young teenagers thinking ahead. But how easy is it to get kids to focus on the future when they’re struggling through a pandemic — and so many of them are hurting?

Robyn Silverman, a child and teen development specialist, is more concerned about getting middle schoolers excited about being in school at all. Schools’ priority, she says, should be on helping studentsfind someone they feel comfortable talking with. “There is such a need for connection, for helping them so they aren’t so untethered,” said Silverman, who hosts the podcast “How To Talk To Your Kids About Anything.” She wonders if asking them to think about careers right now “seems out of place with the times.”

I also wondered if the unformed teenage brain is ready for such forward thinking, so I spoke with Dr. Frances E. Jensen, a neurologist whose excellent book on adolescence has long been my guide. She’s updating it to include lessons from the pandemic.

It’s complicated, Jensen told me. Middle schoolers are “learning machines,” she said, ready to be exposed to a wide range of endeavors that can help them identify strengths as well as weaknesses. “It’s an ideal time to do a broad-based sampling of their skill sets.”

Yet because the age group is so susceptible to new ideas and to authority figures, Jensen worries about too much emphasis on future planning. “They do not have the frontal lobe connectivity to sustain lifelong consequences of their decisions,’’ Jensen said. “They may rush into an area that seems like they are peer-pressured into. I’d be concerned about having a seventh grader declare: ‘I’m going to be a rocket scientist’ … or being railroaded into a track for either university or vocational school.”

At Northview, any and all options are welcomed, without judgment. “The work we are doing on college and career readiness is more about preparing students for life beyond high school,” Rick Doss, the director of secondary education in the district said. Doss believes it’s even more important in the midst of the pandemic. “It gives them hope.”

After middle school, students can take classes at adjacent J. Everett Light Career Center, a 50-year-old sprawling career and technical education complex that trains an array of area high school students for careers including culinary arts, cosmetology, law enforcement and nursing. Slightly more than half of the 557 graduates who attended classes at the tech center went directly to college in 2020 (255), while 232 went straight into the workforce.

The JELCC students, staff and returning graduates I spoke with came from both worlds, and were refreshingly comfortable with the idea that college isn’t for everyone. They had come to visit their teachers and one another over a Chick-fil-A breakfast, and afterwards shared personal stories. Recent graduates like Alejandro Penaloza spoke of the industry credentials he earned studying auto collision and his love for repairing damaged cars, while Alicia Denton described her joy at witnessing a pig’s birth.

“Pigs are just so cute, and they have really nice personalities,” said Denton, now a junior at Purdue University. “Who doesn’t love baby animals?”

Denton had been a lackluster student in middle school. She was more interested in hands-on experiences than academics. A job at a dog kennel convinced her to enroll in a veterinary sciences program at JELCC, but at Purdue, she found cows and pigs more interesting than cats and dogs. After working with swine researchers drawing blood from pigs and joining the farrowing club, Denton decided against a pre-vet track and changed her major to animal sciences.

“Learning what I didn’t want to do helped me figure out what I do want to do,’’ she told her former classmates.

The trajectory of career thinking in middle school followed by actual career training in high school helps Indiana solve another problem: finding sufficient trained workers for good jobs. A lack of talent deters companies from locating in a state where only about 40 percent of workers are in jobs that pay above the poverty line, and where the overall supply of available workers is declining, a recent Brookings Report found. Indiana state Sen. Jeff Raatz (R-Richmond) recently proposed another potential solution: a bill requiring schools to educate students about career options and boosting the number of school counselors.

The state’s average ratio of counselors to students in 2019-20 was about 486 to one, nearly twice the 250 to one ratio the American Association of School Counselors recommends. In Washington Township, adding another full-time school counselor this year at all three of the district’s middle schools brought caseloads down substantially, to between 265 and 300 to one.

Earlier counseling or exposure to careers would probably not have helped Denton, though; she knows she’s a late-bloomer. “My only goal in middle school was to convert my parent’s attic into a living space and live with them for the rest of my life.” (She’s over it.)

K.C. Chandler, on the other hand, is not only glad to have additional counselors at her middle school, she wants to become a counselor or therapist of some kind herself. First, though, K.C hopes to become the first in her military family to finish college. She already has her heart set on New York University. “I’m making a plan so I can do something for myself that my parents couldn’t do,’’ she said.

But in a nod to just how many careers she has already thought about, she added: “I know that my plans could change.”

Photo: Students at Northview Middle School in Indiana use software programs that help them think about their futures. Credit: Liz Willen/The Hechinger Report

Read this and other stories at The Hechinger Report