The share of students returning for their second year of college fell in 2020 to the lowest level since 2012, and the omicron surge and lingering uncertainty around the virus could deepen the dropout crisis

From The Hechinger Report

By Matt Krupnick

February 10, 2022

College took a back seat the moment Izzy B. called the suicide hotline.

Izzy, 18, had spent her senior year of high school online. Then she’d gone straight to online summer school at a local community college near Denver. When in-person classes there started this past fall, she was glad to be back in the classroom and finally experiencing some real college life.

But after Omicron forced classes back online late in the semester, Izzy, who was living with her parents, felt overwhelmed by loneliness; she struggled to focus on her schoolwork and enjoy life.

“We’re at this age where we’re supposed to be hanging out with our friends and socializing,” she said. “It definitely affected my mental health.”

Izzy, whose full name has been withheld to protect her privacy, said she had always earned straight A’s, so the B she received in one class this fall was a sign something was wrong. As she seriously considered suicide, Izzy sought help and moved into her grandparents’ home in Wyoming to be closer to her extended family. And she stopped attending school.

Thousands of other students around the country are leaving college — some because of mental health issues, others for financial or family reasons – and educators worry that many have left for good.

Of the 2.6 million students who started college in fall 2019, 26.1 percent, or roughly 679,000, didn’t come back the next year, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. That was an increase of 2 percentage points over the previous year, and the highest share of students not returning for their sophomore year since 2012. The dropout spike was even more startling for community college students like Izzy, an increase of about 3.5 percentage points.

Researchers usually look at how many college freshmen become sophomores because if a student is going to drop out, that’s when it’s most likely to happen.

While national figures on dropping out of college have not yet been compiled for the current school year, the omicron surge and the continued uncertainty around the virus are elevating concerns that the numbers of students abandoning college could continue to grow.

The rising dropout rate on college campuses has consequences for individual students, their families and the economy. People who leave college before finishing are more likely to face unemployment and earn less than those who complete bachelor’s degrees, and they are about three times as likely to default on their student loans. With fewer college-educated workers to fill skilled jobs, the economy could also suffer in terms of lost business productivity and lower GDP.

“People are worried the shadow this casts will be quite a bit longer than the pandemic itself,” said David Hawkins, chief education and policy officer for the National Association for College Admission Counseling. “This pandemic has really made an impact on a lot of students’ ability to free up time to attend school.”

The wave of students dropping out of college has hit schools of all sizes and characteristics around the country, but in different ways and for different reasons.

Nassau Community College on New York’s Long Island has seen a sharp drop in returning students for the spring semester. College leaders believe some students are tired of online classes, said David Follick, dean of admissions and an assistant vice president.

Even though spring classes are evenly split between online and in-person, demand for the latter is outpacing that for online classes by at least a 2-1 ratio, Follick said. The school is trying to get students to stick around regardless of how they attend classes, he said.

“We’re looking for the silver bullet,” he said.

At private Ohio Wesleyan University, with an enrollment of just over 1,300, a few dozen students decided not to return this fall because the school required vaccinations, said Stefanie Niles, vice president for enrollment and communications.

And while most students have returned to Michigan State University this year, officials are alarmed by a loss of lower-income students and those who were the first in their families to attend college, said Mark Largent, the associate provost for undergraduate education and dean of undergraduate studies. Even though freshman retention is up overall, to 91.7 percent, the share of returning students eligible for Pell Grants (federal aid for low-income students) has dropped more than a percentage point, to 86.3 percent, and the share of first-generation college students has fallen by 1.4 percentage points, also to 86.3 percent.

Those students often have financial burdens forcing them to drop out.

“For one student it might be a car repair, for another student it might be child care,” said Marjorie Hass, a former college president and now president of the Council of Independent Colleges, a 765-member coalition of nonprofit colleges and universities. Congress could help, she said, by dramatically increasing the amount available in a Pell Grant.

Largent said Michigan State has provided additional financial help to the highest-need students, and has also been digging through data to figure out which students might benefit most from some human contact. The school recently emailed about 1,000 students who had yet to register for the spring semester; about 25 percent responded.

Largent worries about the other 75 percent.

“The students I engage with and the students who come back, we can learn what they need,” he said. “But what we really need to study are the students who don’t come back. The students who stop out sort of fall out of communication with us.”

Colleges and universities have good reason to be worried about uncommunicative students, said Sara Goldrick-Rab, a professor of sociology and medicine at Temple University who studies college students’ basic needs.

Out of the country’s 2.6 million students who started college in fall 2019, 26.1 percent, or roughly 679,000, didn’t come back the next year, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. That was an increase of 2 percentage points over the previous year’s level, and the highest share of students not returning for their sophomore year since 2012.

“There is a very significant mental health crisis,” she said. “Students just are not OK. Students feeling lost, students feeling depressed, students feeling anxious — it’s weighing really heavily on them.”

Staff members at Cal Poly Pomona have been so overwhelmed by students’ needs in recent years that they created a chatbot to help answer questions.* If a student mentions certain key words, including suicide, the message is passed on to a counselor, who reaches out personally.

“Students have told us they are leaving because they lost both their parents,” said Cecilia Santiago-González, the assistant vice president for strategic initiatives for student success. “There’s definitely a lot of mental health concerns that have been brought up.”

Several college officials mentioned students are taking fewer credits than before, or registering for a full load of classes and then withdrawing from some of them. Both are possible precursors to failing to graduate.

About 81 percent of students who attend college full time graduate within six years, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, while just 21 percent of part-time students graduate within six years. Students who mix full-time and part-time attendance complete degrees at a 44 percent rate.

Often, all it takes to keep a student from dropping out of college is some personal attention.

Leaders at California State University, San Bernardino, alarmed by the pandemic’s effect on student retention, recently hired re-enrollment coaches to help students who had fallen off the grid. About a quarter of those students registered for classes within three days of being contacted by the coaches, said Lesley Davidson-Boyd, the interim associate vice president and dean of undergraduate studies.

“It’s a lot of hand-holding,” she said. “Students have said things like, ‘Wow, it’s like somebody actually cared.’ ”

Izzy B. said she did not receive that kind of support from her Colorado college. She said she called her advisers repeatedly but never reached anyone. In California, Victoria Castro-Chavez had a different experience — and it made all the difference.

Castro-Chavez had about nine classes left to go at California State University, Stanislaus, in fall 2020 when she felt pushed past her limits. Covid was devastating her family, she was working full time moving trucks at a logistics company, and she was driving more than an hour to sit in a classroom fearing for her life. When her college classes went virtual midsemester, she struggled to learn from a computer screen.

“I was having a really difficult time passing classes and was really burned out,” said Castro-Chavez, 23, a communications studies major who hopes to become a public school teacher. “And I’ve lost four family members to Covid now. It hit me pretty hard.”

As that fall semester wrapped up, Castro-Chavez, who had recently tested positive for Covid herself after losing her aunt and cousins, told her adviser she wasn’t sure she’d be back. The adviser encouraged her to take a short break and then return to school slowly, maybe just taking a couple of classes to start.

The pep talk worked. Castro-Chavez took the spring semester off and focused on her trucking company job. But this past August she re-enrolled, first with a course load of two classes, and then, this semester, three.

It can be challenging getting any student back on track after time off. Just 2 percent of 2020 high school graduates who did not immediately enroll in college showed up in fall 2021, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. The center also found that 30,600 fewer transfer students who took time off from college returned this past fall, a drop of 5.8 percent from the year before.

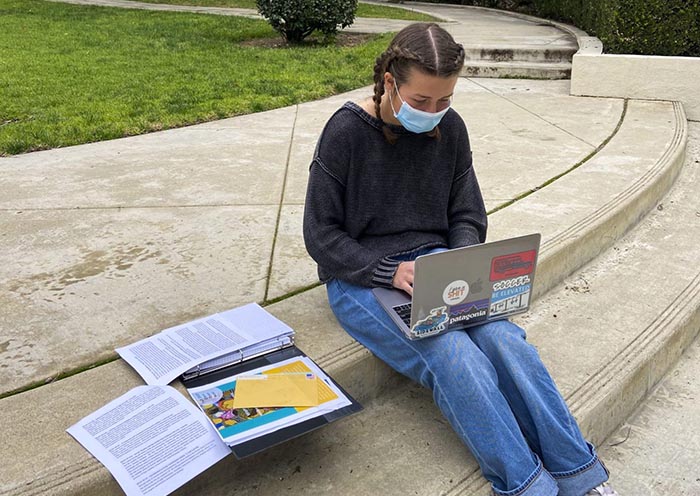

Maggie Callow, 19, bucked those national trends but said it was tough to get into the college mindset after taking a pandemic-induced gap year last year. Having struggled with online classes her final two months of high school in 2020, she just couldn’t fathom spending her first year of college online. So she spent the year at home in Bozeman, Montana, working in a pizza shop, hiking and taking a French class at Montana State University.

Now halfway through her freshman year at Pomona College in Southern California, Callow was deeply disappointed when the college announced the first two weeks of the spring semester would be online. A lot of her classmates are having trouble, she said.

“I think a lot fewer people are going to graduate from college,” she said.

Izzy B., the 18-year-old from Colorado, said she wants to return to college eventually, to become a therapist. But for now, she’s working on her mental well-being.

“We just don’t take mental health seriously,” said Izzy. “It wasn’t until I was thinking, ‘Oh, I’m going to kill myself,’” she said, that she realized she needed to take action to care for herself. “That was a very concrete point.”

Photo: Pomona College student Maggie Callow attends an online class while sitting outside on the Claremont, California, campus. Credit: Image provided by Maggie Callow

Read this and other stories at The Hechinger Report