From K-12 Dive

By Kara Arundel

April 8, 2022

Dive Brief:

Positive student-teacher relationships not only help students but benefit teachers in an interesting way — by leading them to use more challenging instructional techniques, which in turn improves students’ academic achievement, according to research from the University of Missouri.

Using “prosocial classroom behaviors” like showing kindness and compassion increased teachers’ motivation and confidence, research from the University of Missouri shows. It also led teachers to use more challenging instructional techniques that make lessons interesting and relevant to students, said Christi Bergin, a research professor at Mizzou and co-author of the study, which will be published in the journal Learning and Instruction.

Understanding prosocial behaviors’ positive influences on teaching practices could support improved student outcomes, as well as help prevent teacher burnout and stem the tide of teacher shortages, Bergin said.

Dive Insight:

While research exists showing positive teacher-student relationships can boost students’ academic and social development, this is the first study to Bergin’s knowledge that shows how positive teacher-student relationships can impact effective instructional practices.

To better understand the influence of positive classroom relationships on teaching, the researchers analyzed survey data from the Network for Educator Effectiveness, a teacher growth and evaluation system developed at MU’s College of Education and Human Development.

That system is used in more than 280 school districts in Missouri and evaluates teachers on high-impact teaching practices that can lead to student achievement. Those practices under the Network for Educator Effectiveness are:

Cognitive engagement in the content. This refers to the mental engagement of students in learning activities, such as teachers inviting responses from all students.

Critical thinking and problem solving. This includes teachers asking students to explain and justify their thinking or the thinking of others.

Affective engagement in the lesson. Teachers can do this by using materials and activities that are interesting to students and by helping students set achievable but challenging goals.

Instructional monitoring during the flow of the lesson. This practice refers to teachers’ strategies for checking for student understanding while lessons are ongoing and the ability to adjust instruction based on student progress.

The data used in the analysis are based on the student survey of teaching effectiveness in the Network for Educator Effectiveness database. The survey asked students in grades 4-10 to evaluate their teachers on their instructional practices. It also asked students if they believed their teacher cared about them, was accessible to other students in class, and whether they enjoyed learning from that teacher.

The researchers analyzed two sets of survey data from the 2017-18 and 2018-19 school years for 844 general education teachers across grade levels, subject areas and in various stages of their teaching careers, said Bergin, who is also director of the Prosocial Development & Education Research Lab at MU.

The study concluded that when teacher-student relationships are positive, teachers are more likely to use complex and high-impact instructional practices that support higher student achievement.

Those high-impact instructional approaches are difficult to do on a consistent basis, said Bergin. “It’s just hard — really, really hard — and we don’t see a high frequency of those kinds of teaching behaviors, but we know they’re really effective,” she said.

There’s skepticism, however, that teacher-student relationship building would have much influence on student outcomes. Some who are doubtful say focusing on instructional strategies for academic content is the only driver of academic achievement, Bergin said.

“There are a lot of people, both legislators and even some teachers themselves, who say this isn’t important,” Bergin said.

But Bergin said those relationships have multiple benefits and may even be the single best solution to supporting student mental health well-being and to retaining teachers, particularly as school systems recover from the pandemic.

“If you can address … that basic level where you’ve got a classroom in a school that feels like a warm, welcoming, safe place to be, then even kids who are coming with a history of trauma will function better,” she said. “It creates a more positive classroom environment where both teachers and kids want to be.”

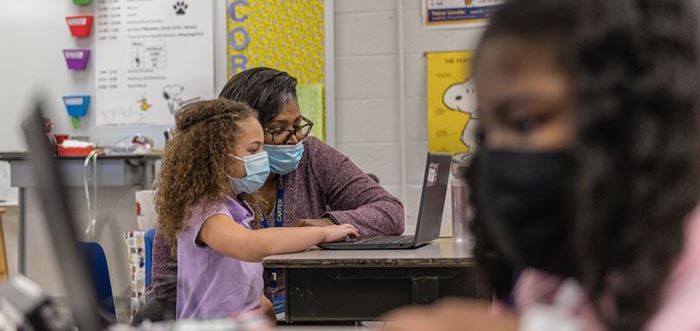

Photo: Jon Cherry via Getty Images

Read this and other stories at K-12 Dive