With its new online academy, Fairfield County — where 90 percent of families live in poverty and 50 percent lack high-speed Internet — hopes to overcome problems with virtual school

From The Hechinger Report

By Sharon Lurye

November 8, 2021

Before the pandemic, Patricia Woodward’s son Zion struggled in school. He was a shy kid, someone who didn’t feel comfortable asking questions in front of the whole class. Even when he needed help, the middle schooler didn’t ask for it. That changed when his school district in Fairfield County, South Carolina, switched to online learning during the pandemic.

“Online, he has no problem asking the teacher a question,” said Woodward. Zion’s grades picked up; by the end of the year, he was on the honor roll. So Woodward was excited to learn that, even after most kids in Fairfield went back to school in person, the district was opening a full-time virtual academy. She enrolled her 14-year-old son there for ninth grade.

The Fairfield County School District might seem like an unlikely place to have embraced virtual instruction. It’s in a small, rural county in the northern part of the state that has been hit hard by the closure of several key businesses over the years — a Mack Trucks plant, a nuclear power construction project, a Walmart — and where 9 in 10 students live in poverty.

When the pandemic arrived, the school district struggled to connect its students to remote learning, as nearly half its households didn’t have high-speed internet. Even when the district handed out personal hotspots, they didn’t work for many families due to poor cell service.

Yet despite all these challenges, the district found something surprising: For some families, virtual learning was still an absolute hit. Some parents, like Woodward, noticed their children worked better away from the distractions and social pressures of in-person school; others enjoyed being able to see their children’s classes. Starting this school year, the district decided to open a full-time virtual academy, one designed to outlast the pandemic.

“This will be the new normal,” said J.R. Green, superintendent of the Fairfield County schools.

Fairfield County is far from the only school district where parents have asked for more full-time virtual options. A Rand Corp. survey conducted in June found 26 percent of districts said they would run a virtual school this year, compared with just 3 percent pre-pandemic. Schools that served primarily families of color — Fairfield is around 90 percent Black — reported particularly high demand from parents for a virtual option.

Yet it’s unclear how many students will remain in virtual learning when the pandemic subsides — or whether they should. Research before the pandemic often showed poorer outcomes for students in virtual schools versus brick-and-mortar ones. Only 3 percent of parents, in another Rand survey conducted this July, said they would send their youngest school-age child to full-time virtual school if the pandemic were over.

If district-run virtual schools do become the new normal, their leaders will have to address the pitfalls that have led to poorer outcomes in the past. Fairfield says it’s doing several things to make the virtual learning system last, including an application process to select the students who are best suited to remote learning; a strong emphasis on live classes taught by district teachers; and allowing virtual students to still have access to in-person sports, after-school activities and hands-on vocational courses. If this small district, despite all the challenges, can find a way to keep students engaged outside the four walls of a classroom, it may shine a light on how other districts can make virtual schools work as well. And the answer to whether a small, rural district can make virtual learning work has key implications for equity in schools across the United States.

“We need to pull the quality up in virtual schools,” warned Heather Schwartz, co-author of the Rand surveys, “so that we don’t have yet another form of splintering, fragmenting public school offerings, where we have a lower-quality track in the form of virtual schools relative to in-person schools.”

For Zion, the school day starts at 9 a.m. and lasts until 3 p.m., with a break for lunch. The teenager’s classes in English and junior ROTC are taught by a district teacher, while history and math are self-paced courses via the online platform Edgenuity. He’ll be able to take career technology classes next semester in person, although his parents will be responsible for transporting him. Zion, who enjoys video games, drawing on his iPad and practicing archery, is quite content with his learning schedule, his mother said.

“He seems to do wonderful virtually. He follows the schedule as if he’s at school,” said Woodward.

Overall, 190 students are now enrolled in Fairfield’s Virtual Academy, taught by 40 teachers. Educators who enjoyed working remotely last year were invited to apply; most of the elementary teachers at the online school teach virtually full time, while the upper-grade teachers split their time between the virtual and in-person schools in the district. It’s just a small portion of students overall, around 8 percent of the district — but higher than what South Carolina has encouraged.

Gov. Henry McMaster pushed hard to return all schools to in-person learning this fall, saying remote learning was “not as good.” This year’s state budget allows only 5 percent of a school district’s students to enroll virtually; if a district exceeds that limit, the state will give only about half as much per-pupil funding for any additional online students.

But administrators said they didn’t have much of a choice. If Fairfield County didn’t offer a virtual option, some families would leave the district entirely and instead enroll in an online charter school. Fairfield fits a national trend: 31 percent of leaders in districts that serve primarily students of color said that parents “strongly demanded” a fully remote option this year, compared with 17 percent in majority-white schools, according to Rand.

“Our parents were so adamant that if we could not provide them with the virtual, then they would seek virtual options elsewhere,” said Brandon Dixon, director of Fairfield’s Virtual Academy.

Still, Fairfield did not let just any student attend the academy; students had to demonstrate that they were a good fit for a virtual environment, based on their grades during remote learning and a recommendation from their principal. Parents had to submit an application and affirm that their child had support at home and consistent internet access — which the parents have to provide themselves.

That last part is one of the biggest barriers to remote learning in rural areas. Almost one in five rural Americans don’t have access to broadband at the speed considered minimum for basic web use, according to a report this year from the FCC.

“The area I live in, the internet is horrible. Most days he was not able to log in,” said Woodward. She had to make a costly switch to another cable company, and now has reliable service.

There are plenty of reasons, however, to question whether states should even encourage full-time virtual learning, except for students who are medically vulnerable to Covid. The research paints a grim picture. The National Education Policy Center, for example, found that the high school graduation rate last year was only 53 percent for virtual charters, which enroll the majority of online students, and 62 percent for district-run virtual schools. The overall national average is 85 percent. A Brown University study last year on virtual charter schools in Georgia found that full-time students lost the equivalent of around one to two years of learning and reduced their chances of graduating from high school by 10 percentage points.

“Before the pandemic, I think there was a lot of skepticism, that maybe it was bad for everybody. Because you look at a lot of the data on virtual learning, and it’s been discouraging,” said Diana Sharp, a senior researcher at RMC Research Corp. who is working on a federally funded study of online learning in three Southern states. Since then, however, schools have realized that while virtual learning is not for everyone, she said, “some kids really thrive.”

Fairfield County is trying to ensure that its virtual program keeps the same quality standards as its in-person schools by making sure that, for the most part, students continue to follow a normal bell schedule and regularly interact with the teacher. There are live classes for most of the day, every day except Thursday.

“Our model was probably one of the most difficult models to implement, but it was also one of the most effective,” said Superintendent Green.

In contrast, a survey this spring of educators in 17 virtual schools established before the pandemic found that only 3 percent of virtual teachers said their classes were mostly synchronous.

The only exception to the live learning model at Fairfield is that high schoolers also take some courses via the self-paced Edgenuity platform. However, Fairfield didn’t have the staff to create fully virtual classes for every high school course, and South Carolina requires districts to pay teachers extra for hybrid courses. The district had used Edgenuity before the pandemic and decided to keep using it for some high school courses.

Woodward said she was concerned about the Edgenuity courses, as Zion has struggled to know who to reach out to if he has a question about an assignment. Some parents in other school districts that have used Edgenuity have criticized the quality of those courses, and research isn’t clear on whether they are effective. Edgenuity spokesperson Tim DeClaire stated that there is an option for schools to pay for access to more instructional services from the company, including on-demand tutoring and a teacher who is available to respond to all student communications within 24 hours, but the vast majority of school districts, including Fairfield, opt to purchase only the self-paced courseware.

Still, Woodward says Zion’s grades are good, and she expects to keep him in virtual school next semester. Beyond that, she’s not sure.

“There’s a lot of things he’s probably missing out on by not interacting with more people,” she said.

Fairfield County teacher Claudia Fletcher-Lambert has gotten into the swing of things when it comes to virtual education. In one math class in September, she was teaching her fourth graders how to add multi-digit numbers. Twelve faces stared out from boxes on the screen, joining her from bedrooms and living rooms. Little girls with beads in their hair held on to notebooks and pencils, ancient tools that still prove useful in the digital era; a boy lounged on his stomach with his legs swinging up and down; grandparents in the background watched over their charges.

Fletcher-Lambert, sitting at home in front of a poster that said “You Are My Sunshine,” made the lesson feel like a game show. She explained how to expand the numbers, for example turning 1,234 into 1,000 plus 200 plus 30 plus 4. She spun a virtual wheel on screen to pick a number, played applause sound effects, and called out to the class, “Write that number!”

The kids wrote out the expanded form of the number in the chat box; Fletcher-Lambert called out those who got the right answer by name: “Great job, great job!” She asked the students to break down 1,780 plus 173 into expanded form, add them up, and write their answers on a virtual sticky note in a shared, interactive whiteboard.

While the kids worked, Fletcher-Lambert kept up a steady stream of encouragement, commentary and questions to keep them focused, knowing how easy it is for kids to drift off when they’re watching a screen most of the day. “Breaking your numbers down — good job, Shanise, good job, E’Nija.” “De’Arte, you only broke one answer down. Where’s the second number?” “Rodreikus, unmute and explain your thinking for me.”

Fletcher-Lambert said it’s crucial that her class size is small, so that she can keep tabs on all her students. When she reached out to virtual teachers in other schools for tips, she found some of them were working with classes of 40 students.

“It is impossible to have 40 kids working with virtual at the same time,” said Fletcher-Lambert, especially when those students have diverse learning needs.

While Fletcher-Lambert always loved using technology in the classroom, Kim Yarborough, a sixth grade teacher, was surprised to find she was well suited to online learning. She said, “I have thoroughly enjoyed the start of this school year probably better than any school year I’ve had” in her 28 years of teaching.

Why is she happier? “I don’t have to decorate my classroom,” she laughed.

But more seriously, Yarborough added, she’s noticed that the 18 students in her class are far more comfortable outside of the social pressures of the classroom. Students are more willing to ask her questions through a private message. If Yarborough needs to help a child who’s struggling with a lesson, they can work together in a breakout room without drawing anyone’s attention. Bullying, she’s noticed, has disappeared.

“Students aren’t judging each other like they do during face-to-face instruction,” said Yarborough.

Skylar Walker, a soft-voiced 11-year-old in Yarborough’s class, said she struggled in school with “a lot of girls distracting me and a lot of drama.”

“I’m learning more when I’m in virtual, because I can focus a lot and I’m by myself,” she said.

Her mom, Kayla Hartpence, agreed that Skylar has “thrived” academically since she started learning at home. “I think that was because of less distraction,” she said. “I think it’s a little bit more intimate because it’s just her in her room by herself.”

Jennifer Greif Green, who co-wrote a Boston University study on bullying during the pandemic, said, “A lot of bullying occurs during unstructured times, times like recess or during lunch in the cafeteria.” The study found Google searches for both school bullying and cyberbullying plummeted while the majority of U.S. students were learning remotely.

“The virtual environment and experience eliminate a lot of those unstructured times for students,” she said, “for better and for worse.”

The flip side is that less unstructured time also means less time spent just hanging out with friends at the playground or in the hallway between classes. Skylar’s mom says she still wants her daughter to go back to regular school next year so that she doesn’t get too “sheltered” from unstructured experiences.

“I want her to socialize. I don’t want her to be too comfortable in her room,” said Hartpence.

Fletcher-Lambert, the fourth grade teacher, said she understands it’s important sometimes to pause the carefully orchestrated academics and let the kids start a free-flowing conversation. Sometimes she’ll create breakout rooms where her students don’t have to do anything but sit and chat.

“Sometimes I just look at their faces. …‘Can I just speak to you for a minute in the breakout room?’ Sometimes they’ll say, ‘I’m so tired today.’ We have a lot of conversations,” she said.

It’s hard in those moments to not be able to sit right next to the kids, look at them face-to-face, give them a hug. Creating those connections with students, supporting them even from afar, will be the biggest test of whether districts like Fairfield County can make virtual learning work even after the pandemic fades.

“I think it’s the biggest challenge for us now,” said Fletcher-Lambert. “That missing piece of human interaction.”

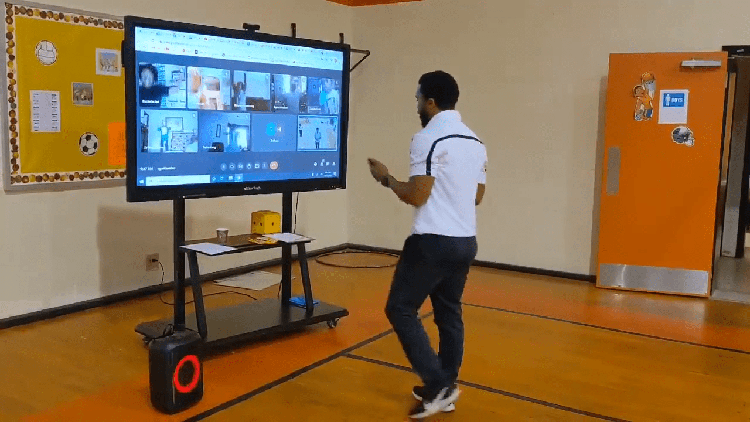

Photo: A gym teacher at Fairfield County Schools in South Carolina leads a virtual P.E. class for kindergartners and first graders. Credit: Image provided by Fairfield County School District

Read this and other stories at The Hechinger Report